It

was one of those awful moments of self-awareness. My husband and I had just

discussed a money issue, and things were a little tense. “I just wanted to have

a conversation about it,” I said. “We didn’t

have a conversation,” he said. “You talked

at me about it.” Painfully true.

Luckily, we have 30+ years of water under the bridge and lots of practice at

forgiving, so all is well. But it made me think about coaching……

Coaching

is about conversations. When we talk about teaching, there’s an exchange of ideas,

with both (or all) parties offering content for the dialogue. A shared belief

that teaching is such important and complex work that we will never do it

perfectly invites rich professional conversations.

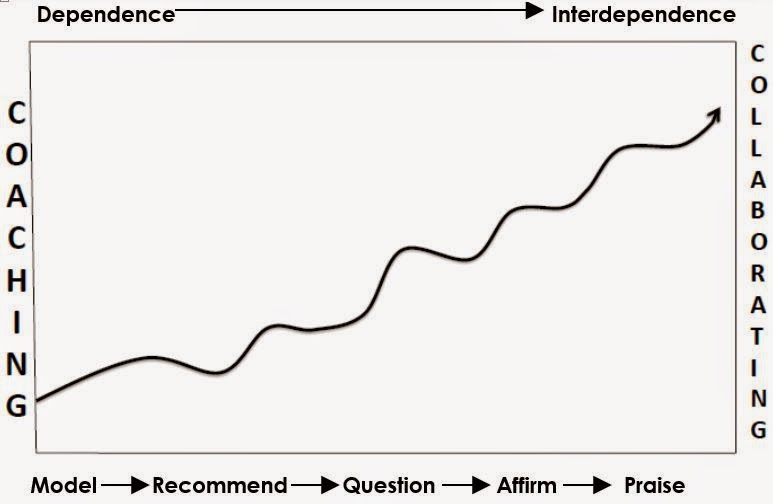

Other

than modeling, all of the coaching moves in the GIR model should be dialogic in

nature. The back-and-forth of conversation is what leads to understanding and

changed practice. Let’s take a closer look at asking questions as

dialogue. Here's a non-example:

This

week, I asked a student teacher I was working with an admittedly great question! I’d been in her room

during one of those magical discussions where students build on one

another’s ideas in an authentic way. Kids were describing what a main idea is,

and they really helped each other learn. Not much later in the lesson, however,

the magic was gone and the discussion felt forced. So, in our debrief

conversation, I wanted to take the intern back to the magical spot for

analysis. I asked, “What’s your hypothesis about why that magical interaction

happened?” You’ve got to admit, that is

a good question! But here’s where I fell

short in my obligation as a coach. After only a few seconds of wait time, I

jumped in and asked if I could share my hypothesis. That was a conversation

killer! When I suggested that her open-ended question and spontaneous and

authentic response to a students’ answer had sparked the magic, the student

teacher nodded and smiled. But I had robbed her of the opportunity of figuring

that out for herself, which would have been much richer learning.

Quickly,

I knew what I should have done, but

it was too late. I should have waited

longer for her to respond, even though her peers were all staring at her (that

would have provided a good model for them, right?). If silence persisted, I could have scaffolded her thinking with

additional questions that took her back to the moment and helped her relive and

reflect. But I didn’t --- and I know better than that!

So,

I resolve to “walk the talk” and engage in two-way conversations with those I

am coaching. When I give a less-confident teacher a recommendation, it’s going

to be more effective if couched in dialogue. Even praise will hit its mark in a

more meaningful way if it’s part of an exchange of ideas.

And,

if my husband’s lucky. I might just bring my coaching skills home. J

This week, you might want to

take a look at:

The

Ted Talk about body language has important implications for coaches and

teachers:

Getting

students’ attention without saying a word (1 minute worth sharing):

Ideas for using technology to

teach grammar and sentence fluency:

Someone’s

version

of the 50 Top books for teachers – how many have you read?

http://www.eschoolnews.com/2014/06/13/50-top-books-teachers-545/2/

That’s

it for this week. Happy Coaching!