In

the movie, The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy

seeks help from the all-powerful Oz, hoping he can solve her problems and those

of her friends. After she lifts the veil to reveal a bumbling man pulling

levers, her hopes are dashed. However, Oz provides all they need: heart, brain,

courage, and power to go home. Revealing the mechanisms behind the scene did

nothing to reduce the assistance that Oz could provide, even though he felt

exposed when the veil was lifted.

In

the movie, The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy

seeks help from the all-powerful Oz, hoping he can solve her problems and those

of her friends. After she lifts the veil to reveal a bumbling man pulling

levers, her hopes are dashed. However, Oz provides all they need: heart, brain,

courage, and power to go home. Revealing the mechanisms behind the scene did

nothing to reduce the assistance that Oz could provide, even though he felt

exposed when the veil was lifted.

Like

the Wizard, for years I kept the veil drawn on the help I was providing as a

coach. I’m not sure why. Perhaps I was afraid that being transparent about my

coaching moves would make the process feel less authentic. And maybe there’s

some truth to that. But I’ve found that when I have lifted the veil and shared

the GIR Coaching Model, it has been well received by the teachers I’m working

with.

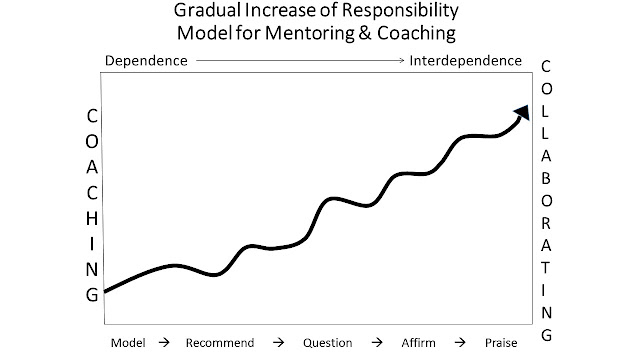

The

Gradual Increase of Responsibility Model for Coaching and Mentoring (below),

turns the familiar GRR teaching model on its head by putting the focus on the

increasing independence of the learner – in this case, the teacher. I’ve reaped

benefits by sharing the model – and the goal – with teachers I’m working with. At

the beginning of a coaching cycle, when I’ve said, “Why don’t we start with me

modeling this for you,” and pointed out that our goal was for her to be doing

it on her own, with me sitting back and praising, the teacher felt confident

about the path forward. “It’s so empowering,” one teacher said, while examining

the GIR model. She knew that the support I’d be providing would be gradually

reduced through mentoring moves that offered less and less support: after

modeling, recommending; then questioning; and finally, affirming and praising.

These teachers were excited to see their progress charted as I used

less-directive coaching moves.

If

you’ve had the veil drawn on what you’re doing as a coach, consider whether it

might be helpful to share your process and your goals for the coaching cycle. A

novice teacher will likely feel inspired by the faith you have in her ability

to reach the praising stage. A more

veteran teacher may likewise feel encouraged and welcome your explanation as the

openness of two professionals talking about their craft. With the veil lifted,

you may feel empowered, too, by the transparency you are providing.

This week, you might want to

take a look at:

Tips for successful parent teacher

conversations:

Why culturally-relevant

literature is important in this NCTE article, “No Longer Invisible”:

This spotlight on

English Language Learners:

Taking the formula out of non-fiction

writing:

Procedural Writing in math:

That’s it for this week. Happy

Coaching!